Copied from Beneath Ben Lomond’s Peak: A History of Weber County, 1824-1900, pg 276-279.

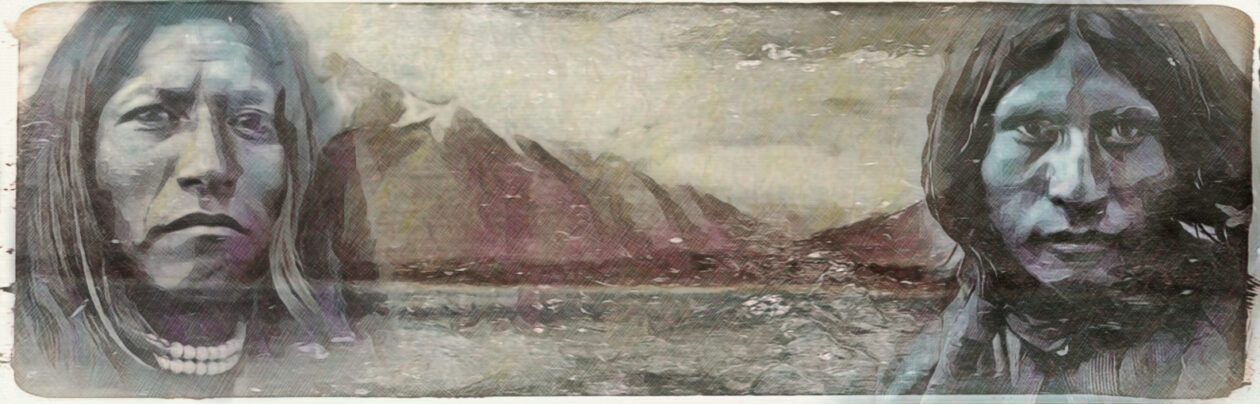

EXPERIENCES OF JANE HULL RILEY

(This information was received from two daughters of Jane Hull Riley, Mrs Bertha Clancy and Mrs Hattie Graham, and from Robert R. Hull, grandson of William G. Hull. Compiled by Annie H. Jordan)

Franklin, the first permanent town in Idaho, was settled in the spring of 1860, by a group of Mormon colonists. They were sent there by Brigham Young to colonize that portion of his proposed empire.

Of all the problems connected with pioneer life, the most difficult one during the first three years at Franklin was the Indians. Near the settlement lived a tribe of Shoshones who immediately began to cause the pioneers no end of trouble. Before leaving Salt Lake the colonizers had been instructed by Brigham Young to feed the natives. This they tried to do. In December 1862, the situation became unbearable. Food was extremely scarce, and the demands of the red men increased. They threatened to massacre the settlers. Also, the Indians made attacks on immigrant parties headed for California, and on others coming from the Montana mines to Utah. Therefore, several requests were sent to Colonel Patrick E Connor at Fort Douglas to bring soldiers for the protection of the white people.

Meanwhile at Franklin the Indians insisted on having more food. William G Hull, a young man twenty years of age, served as interpreter for the colony. He held a council with the savages and endeavored to make them understand that the settlers had no more grain. The Indians, however, still demanded the grain. Therefore, William and his brother Thomas loaded in a wagon the last nine sacks of wheat owned by the settlers and went out to meet the red men who were just outside the town. It was now January 1863. These two young men plead with the Indians, telling them it was all the grain they had and it was their seed for the spring planting. The red men only laughed and insisted on taking the grain.

Finally, seeing that they could stall them off no longer, the boys loaded one sack of grain on an Indian pony. They were in the act of loading another when Hull saw in the distance the soldiers coming. He called “soldiers,” in the Indian language, and pointed in the distance. The natives cut the sacks loose, spilling the grain all over the ground, and fled.

Colonel Connor’s force found the Indians encamped in a ravine leading up from Bear River through an ascending plain toward the mountains, the main camp being located about fifteen miles from the town of Franklin. For four hours a fierce battle was waged, during which the savages fought most desperately. Nearly 400 Indians were slain, including many women and children. It was reported at the time that only fifteen of the warriors escaped.

After the battle was over and Colonel Connor and his troops had left, William Hull and others went over to the battle ground looking for traces of life. They found two Indian women, two boys, and one little girl. All of them except one of the boys were badly wounded. They were immediately taken to Franklin and given first aid. One woman and one boy soon died. The other woman recovered and made her home with the people of Franklin for several years. The other boy was adopted by Bishop Hatch, and the little girl, badly wounded, was taken by William Hull to the home of his parents. There she was nursed back to life by his mother and sisters.

The life of this little Indian girl, whom they named Jane but called her Jannie, became a part of the life of the Hull family. Her adopted parents were Thomas and Mary Benson Hull, who had eight other children, four boys and four girls. For several months after Jannie came into the Hull family, she could not speak one word of English; in fact, she would not even try. William tried very hard to teach her. On April 7, 1863, he left to go back to Omaha to help bring an emigrant train across the plains to Utah. When he returned in the fall, he was delighted to have the little Indian girl meet him on the outskirts of town with several other girls and greet him in English. While he was gone East, Jannie had grown well and strong; but she carried six scars on her body throughout life as a result of being wounded at Battle Creek.

The entire Hull family were very good to the Indian maiden. Mrs. Hull took her to church and sent her to school. At first she was timid and backward, not mixing very much with other children. As time passed, she adapted herself to the white man’s ways. She grew up a kind, lovable, obedient daughter, willing to share the work of the home. She was dependable and honest, and loved and respected by the people of the community.

Jannie was always afraid of Indians. Many times she ran and hid when they approached the home. One time, about 1867, several Indians came to town, and recognizing her, tried to get her to tell of certain plans of the white men. They also told her of many things they wanted and what the result would be if their demands were not granted. They even threatened her life if she refused to divulge her adopted peoples’ plans. She went directly to her foster father with the information. The Indians were apprehended before any damage was done. On several occasions, endangering her own life, she went for help and thereby saved the lives of the white people.

In 1870, Thomas Hull, his wife and son, Brigham, and Jannie, the only two unmarried children, moved to Hooper. They built an adobe house across the street from where the old north school was later erected. Jannie was then twelve or thirteen years old.

Six years later her foster mother died. This death affected the Indian maiden very much. She had learned to love Mother Hull as her own. Jannie now went to live with William Hull and family who had moved to Hooper in 1872. A few years later, romance came into her life which resulted in her marriage to George Heber Riley, a young man of a fine pioneer family of Hooper. Her good mother-in-law, Harriet Emmett Riley, was indeed a ministering angel to this young Indian. She took care of her at the birth of all her children, giving her the loving care of a real mother. The Riley family was very thoughtful of her in every way.

Jane Hull Riley reared a large family of ten children. She was a patient, kind, ideal mother, having a genuine love for her children. She believed that her first duty was to make a good home for her family. She also taught them to pray and sent them to school, Sunday School, and Primary. The people of Hooper testified to the beauty of her children in their youth with their dark eyes and hair and lovely complexions. She was an excellent wife and an immaculate housekeeper. It was her joy to cook a delicious meal for her family and friends. Many a child has been delighted with cookies received when he visited her home. They now tell about it as grown men and women. Hers was a pioneer life of hardships, sacrifice, work and toil, but she lived it well in her quiet, gracious, uncomplaining way. She died on October 19, 1910.